TJI Blog

Where the TJI team posts blogs about our data, publications, analyses, and code.

2021 Deaths in Custody decline from previous year

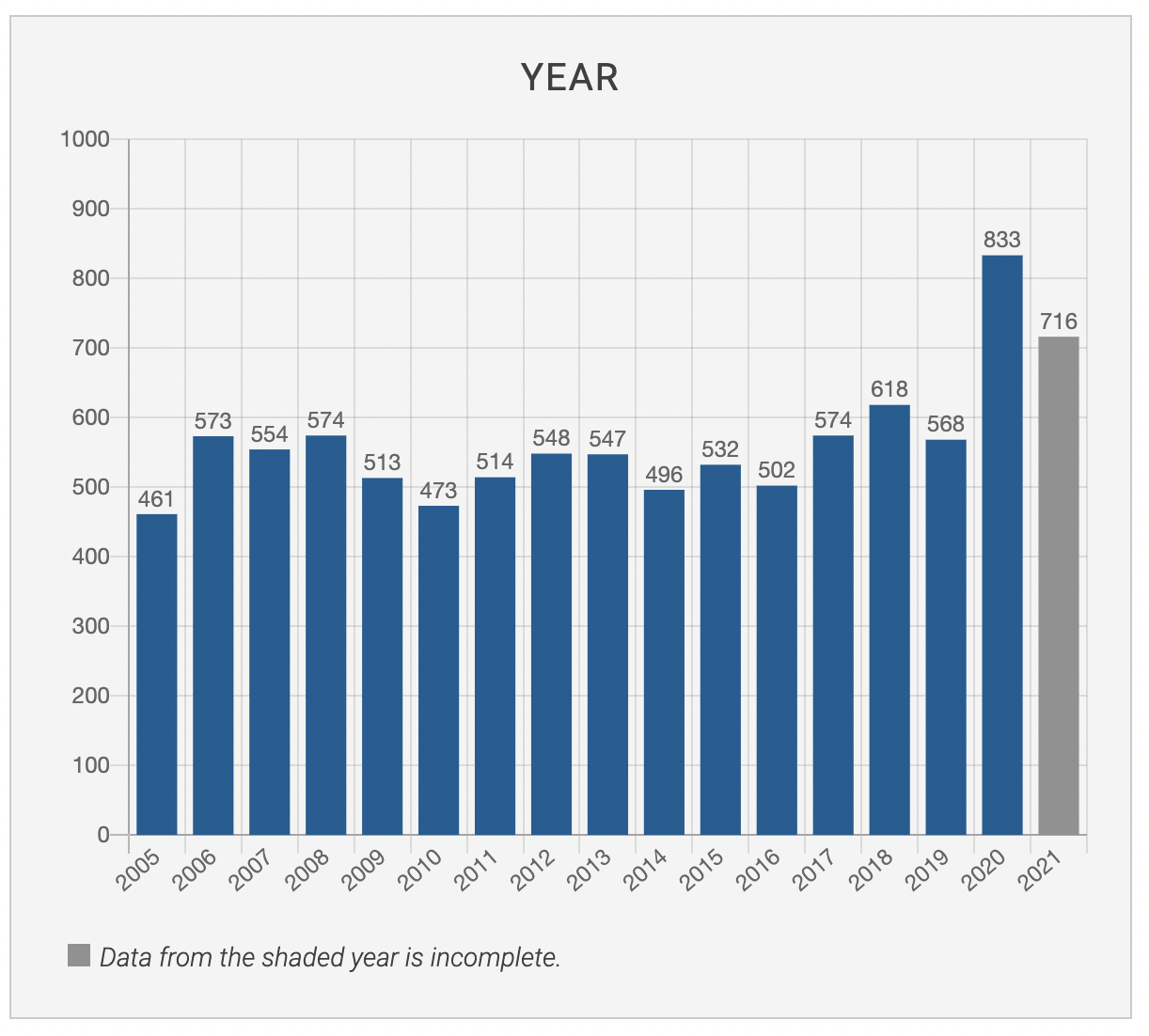

May 24, 2022The good news*: the number of people who died in the custody of Texas law enforcement went down in 2021 after peaking the previous year.

The bad news: 2021's total — 906 deaths, according to reports filed with the state of Texas through May 1, 2022 — was still higher than every other year but 2020.

Deaths in custody of law enforcement, including anything from a deadly shooting by a law enforcement officer or an overdose in the back of a patrol car to a death by suicide or medical cause in a prison cell, must be reported to the state of Texas within 30 days of occurring. Based on those reports, which TJI tracks every month, there were an average of 677 Texas deaths in custody from 2010 to 2019. Then, due undoubtedly in part to the 2019 coronavirus, deaths in custody rose nearly 45% higher than the prior 10-year average before dropping slightly in 2021.

The leading manner of death in 2021 continues to be of causes deemed “natural,” though the percentage of deaths by natural causes was fewer than in 2020 and for 2010 - 2019. The percentages of deaths due to “other” causes and “accidental” causes were slightly higher in 2021 than in 2020 and for 2010 - 2019, while deaths due to “homicide” were slightly lower. As in previous years, the highest concentration of custodial deaths in Texas took place among individuals over the age of 60.

* Good/bad news labels based on assumption that reducing the number of deaths that occur in the custody of Texas law enforcement is a positive thing

law enforcementdata oversightCOVID-19 drives spike in deaths in Texas prisons and jails in 2020

December 22, 2021

According to custodial death data, 2020 was the deadliest year on record for people who were incarcerated in Texas prisons and jails (see graph above). At least 830 individuals died in Texas prisons and jails, an increase of 46% over the previous year (2019), based on reports filed with the Texas Office of the Attorney General. This increase was largely driven by the coronavirus, which – agencies self-reported – killed at least 278 people in prisons and jails last year.

Broken out on its own, COVID-19 was the second-highest cause of death in jails and prisons, accounting for 34% of 2020 deaths, behind all other natural causes/illnesses at 50%. Excluding COVID-19 fatalities, deaths from natural causes in 2020 were consistent with previous years. Historically, natural causes account for more than three quarters of deaths in jails and prisons. Between prisons and jails, prisons saw both the highest number of deaths overall (84%) and the highest concentration (92%) of COVID-19 deaths. Among incarcerated individuals over the age of 50, COVID-19 accounted for at least 40% of deaths.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in the U.S., there was a brief acknowledgement of the unsanitary and cramped conditions – which are also a breeding ground for the novel coronavirus – characteristic of U.S. detention centers. States across the country dramatically downsized their incarcerated population and granted compassionate release to those already infected with (or more likely to die from) COVID-19. However, in Texas, explicit policies to reduce populations during the pandemic were few and far between, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

The data on conditions in Texas facilities was often inaccurate and unreliable. The tracking dashboard maintained by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice occasionally had disclaimers stating that the data was unreliable. TDCJ also published announcements when incarcerated individuals and employees died of COVID-19, but those posts have become sporadic at best. Additionally, agencies also took longer to file their custodial death reports, some showing up months after the 30-day deadline as required by state law. Lastly, changing, incomplete or vague reporting of the precise cause of death made it difficult for watchdogs, like TJI, to capture all COVID-related deaths in their reporting. For example, during the pandemic, TJI started tracking deaths that are reportedly caused by “bronchopneumonia,” a cause that didn’t exist much on reports before 2020.

Beyond being a tragic example of the deadliness of COVID-19, the spike in deaths within Texas jails and prisons in 2020 raises questions about the conditions that make those facilities uniquely vulnerable to outbreaks. The lack of disinfectants and poor medical care, in conjunction with cramped conditions and the negative impacts of living in a high stress environment, all contribute to making jails and prisons inherently unsafe and, in 2020, increasingly deadly spaces. Worst of all, this trend doesn’t seem to be slowing down: 2021 has already exceeded 2019 totals by 6%, with 600 deaths reported as of the end of October.

NOTE: For the purposes of this analysis, custodial death reports were cross-referenced against manually-gathered reports from media and other law enforcement sources to determine whether a death was due to COVID-19. Data was pulled in the first week of November 2021.

covidincarcerationCOVID-19 data scant during Delta variant wave

October 4, 2021For months, Texas has been battling the highly contagious Delta strain of the coronavirus. After a surge in the beginning of 2021, deaths due to COVID-19 were somewhat low in the spring – but then they started to climb.

And despite the rise in cases undoubtedly affecting individuals incarcerated in prisons and jails, who are particularly vulnerable to die from COVID-19, the actual reporting of infections and deaths in Texas lockups has mostly stopped.

For many months since the start of the pandemic, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, which is responsible for ensuring county jails operate within state law, had asked jails to file daily reports on whether (and how many) infections were detected among staff and incarcerated individuals. However, that practice ended in June, when TCJS informed jails that the reports were no longer required.

Throughout the pandemic, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, which oversees prisons, periodically announced deaths of employees and incarcerated individuals online. Yet no deaths of incarcerated individuals have been announced since mid-June.

Amid this dearth of data on COVID-19 deaths in Texas lockups, since mid-June, more than 13,400 Texans have died from the coronavirus, according to state data. Also since mid-June, the pandemic has killed at least 31 people who worked for county sheriff's offices and TDCJ, according to media sources, agencies and the Officer Down Memorial Page.

So just how many people have died of COVID-19 in Texas prisons and jails during this latest deadly wave? At least 18 – according to custodial death reports that agencies are required by state law to file within 30 days of a death. But the true number? It will take months to know for sure.

coviddata oversightJoin Our Team

July 27, 2021TJI functions thanks to talented volunteers who work collaboratively to build and maintain our website and data tools. Our team meets weekly – remotely and, when volunteers in Austin are comfortable doing so again, in-person – and keep in touch during the week on Slack and email. We are lucky to have consistently had amazing volunteers, and we are looking to add a few people to the mix.

Our volunteers have a variety of skillsets, backgrounds and levels of experience. Frequently, we learn from and teach each other during our weekly meetings and in one-off conversations. We'd love to welcome folks who can work on existing projects like automating our data collection processes, incorporating maps into our existing data sets and applying our new style guide to our use of colors in existing charts, and we're also looking for people to fill these new roles:

-

data visualization designer/architect for new project that incorporates several sets of data regarding populations in county jails over time;

-

data architect to coordinate with corporate volunteers on automation tool;

-

SEO and Google Analytics whiz

Does any of this sound like you? If so, please fill out this form, where you'll also find the fine print on our stack.

team-

Texas Attorney General’s Sites for Death and Shooting Reports Go Dark

June 15, 2021For six weeks this spring, the Texas Office of the Attorney General’s websites that house reports on officer-involved shootings and deaths in custody were malfunctioning, cutting off access to records that detail important (and often lethal) interactions between civilians and law enforcement.

Every week, law enforcement agencies file dozens of reports with the Attorney General’s office that provide a glimpse into incidents like an officer’s use of deadly force, an incarcerated individual’s death, and shootings in which an officer is shot or shoots a civilian, resulting in an injury or a death. The office then posts these reports online – except that hasn't happened since severe winter weather hit the state and all updates ceased.

On Feb. 15, I noticed that both repositories were empty. After a couple of weeks, some reports appeared, and by the end of March, both collections appeared to be fully restored.

State laws require agencies to file these reports with the Texas Attorney General within 30 days of an incident in which an officer is shot or shoots someone, or when someone dies in their custody. The office then posts these reports online – a move stipulated by statute for the officer-involved shooting reports.

Said another way: By not publishing the reports on officer-involved shootings, the OAG was in violation of state law.

Back when the sites went down, I sent an email informing the office as such, as I have done in the past. On Feb. 22, I heard back:

Hi Ms. Moravec,

The OAG was closed all last week due to the weather and the electrical outages. I have reported the situation to IT this morning and they let me know they are working on it.

As soon as I hear back from them, I will let you know. Thank you for reporting this to us.

IT then followed up that “Salesforce recently rolled out another update,” which caused the outage. About a week later, many of the cases had been restored, but hundreds from this year and last year remain missing, which I again reported to the Attorney General’s office.

This outage means that when someone dies in law enforcement custody – such as Marvin Scott III, 26, who died in the Collin County Jail in March, the custodial death report that officials must file related to the death isn't visible online. That being said, reports (once they are filed) and data are still obtainable through open records requests. On March 22, we submitted an open records request to the Attorney General's office for the custodial death report for Marvin Scott III – not even knowing if it had indeed been filed. We received the report the next day and posted it publicly here.

While the sites were down, TJI continued to obtain data on these incidents from the Attorney General’s office through our standard monthly open records requests. During the outages, the data on our site was kept up-to-date to reflect all filed reports, although the actual reports were unavailable.

This lag in transparency took place during a tenuous time in Texas, with the novel coronavirus still a threat, particularly to those who are incarcerated, and amid winter storms that knocked out power for millions of Texans and claimed the lives of at least 57 people. It remains unclear exactly how the storm affected the health of those behind bars, but we promise to keep apprised of this situation and always share what we find.

data oversightUsing Markdown and GitHub for Blogging - Part 1

May 16, 2021Our TJI volunteer team has grown over the last year. We have new volunteers who are working on various projects. With this growth, I've started thinking about a blog where volunteers like myself can document and publish our work easily and efficiently.

Blogging is useful in many ways. First, it highlights a volunteer's work in their own words and gives them credit. This process enables the continued professional development of team members who are interested in learning new things. Second, it allows us to communicate with various readers such as tech workers, policy makers, social scientists, community members, and so on. This way, we can help other non-profits like us as well. Finally, similar to our existing workflow, drafts can be reviewed by our team members before publishing so that our writings are robust and knowledge transfer happens naturally during the process.

Blogging in markup languages

We discussed how to formalize a publication and review process. Previously, we've used Google Docs to write, edit, and review our drafts. Our review process has been pretty standard; reviewers commented on a certain part of a draft, which was shown in the margin.

Instead of Google Docs, I suggested using markup languages such as Markdown or reStructuredText, which are commonly used in software development. Compared with existing word processor software such as MS Word or Google Docs, using markup languages can be somewhat challenging to first-time users. You need to learn the syntax and sometimes a bit of html and css knowledge is also required to get the style right.

However, I think these benefits outweigh those challenges:

- It is possible to use a version control tool to track changes easily.

- Every styling is written explicitly (e.g.,

**<text>**for bold text) and thus easily discoverable. - It is easy to include code snippets in the post and they are automatically rendered in a standardized way.

- It is easy and fast to publish drafts online.

- With a document builder, we can convert a draft into various printable formats.

Reviewing blog posts on GitHub

Once blog posts are written in markup languages, we can use a version control system such as git to track changes. This makes the blog review process similar to code review in software development. Then it's possible for our volunteers to collaborate on a blog post through GitHub.

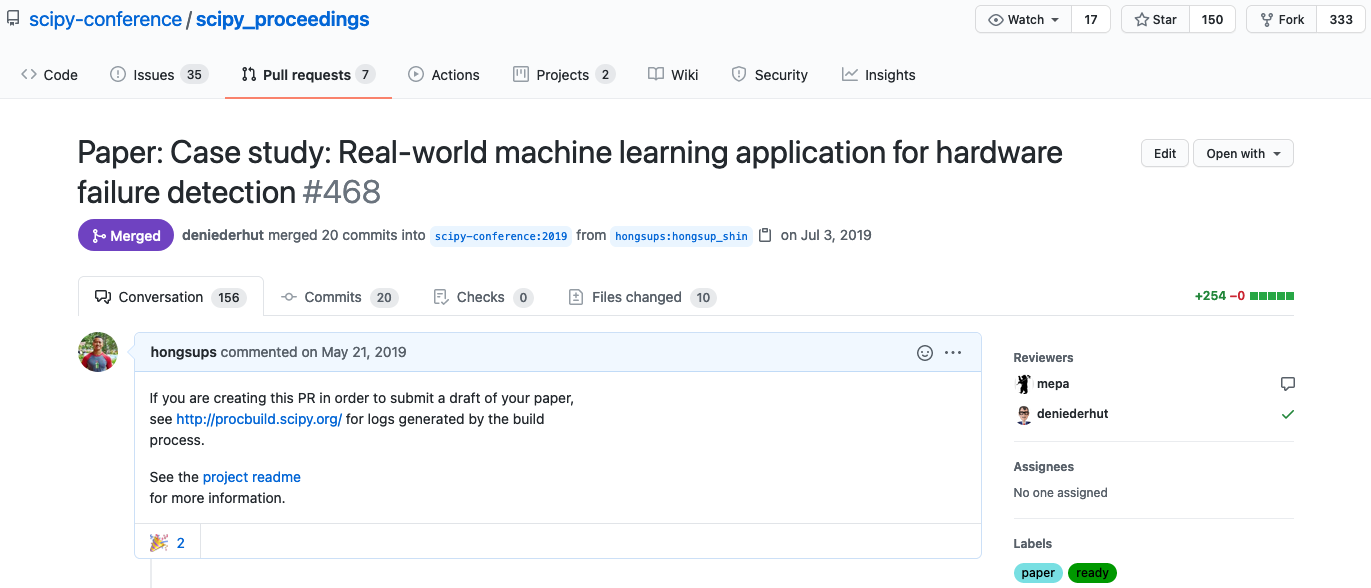

Some of you may feel skeptical about this approach because you might know GitHub primarily as a platform for code repositories. I understand this perspective, because that's exactly how I felt when I was asked to submit a manuscript as a ReStructuredText document at the Scientific Computing with Python (SciPy) conference in 2019. However, after going through the process from both ends – as an author in 2019 and a reviewer last year – I've come to really enjoy the process.

At the SciPy 2019 conference, I submitted my manuscript as a pull request to their proceedings repository. I wrote a manuscript as a ReStructuredText file and attached figures as separate files, and two reviewers reviewed my manuscript.

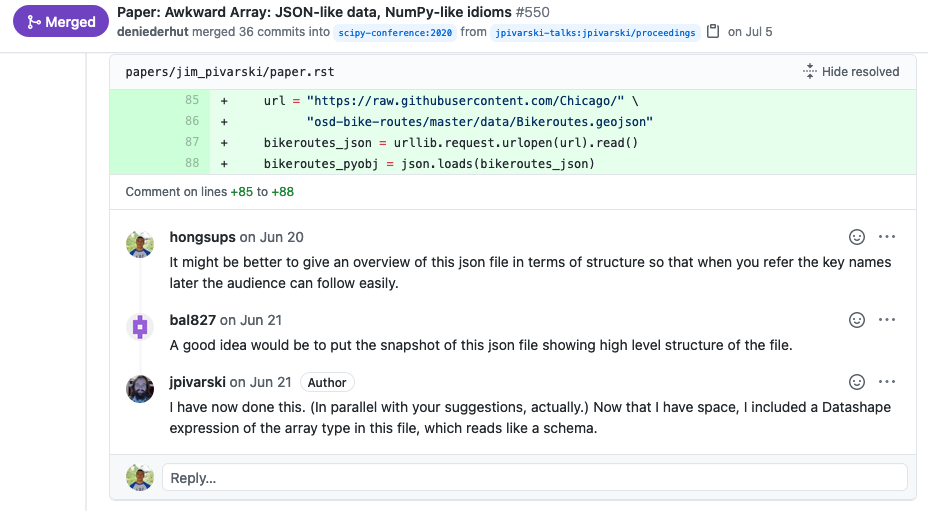

Last year, I was on the opposite end of the process and reviewed a paper that was submitted as a pull request.

Based on these experiences, I found the following benefits:

- Exact exchanges between the original and the revised are easily discoverable. This is useful especially if a manuscript goes through multiple revisions.

- Switching to a previous version of the manuscript is seamless. It's easy go back and forth between different versions of manuscripts and this prevents people from creating multiple copies (files) of the manuscript.

- Communications and decision-making processes are tracked with the manuscript. MS Word and Google Doc don't provide much physical space for lengthy communications. Thus you often need to accept previous comments to remove the visual clutter and then those comments disappear. You can use email but then your communication exists separately.

- Non-authors can't edit the manuscript without authors' permission. Only authors can make changes to the manuscript. This doesn't mean that they have all the power though because reviewers' approval is needed for publication (i.e., pull request merged).

- Group communication is available. Normally reviewers don't talk to each other but comments can make a group communication easier. This way, we can have a discussion and develop better ideas together. It also prevents reviewers from being siloed.

- Review process is transparent. Because of GitHub's great traceability, public repositories like ours will allow others to see our review process including the communication history.

- Reviewing technical material is easy. It's easy to incorporate code snippets, hyperlinks, etc. and they are all visible in the manuscript.

- Everything exists in one place. Normally non-document type files exist in a different place. However, this way, we can keep our blog post, documentation, and our code all in the same place.

How it Works

Authors

Write a blog post in a markup language by using any text editors. Once done, submit the manuscript for review as a pull request. At the pull request page, assign reviewers. To write a post in a markup language, you have to know the syntax. To submit it as pull request, you have to have a bit of knowledge on how to use git.

Reviewers

In a pull request page, you can check who are assigned as reviewers. If you are assigned, you will see your ID. GitHub Docs has detailed information on how to review changes. Keep in mind that even though you will have to read the manuscript in a markup language format, you can still check its rendered version by clicking "View File" option in the menu.

From Pull Request to Merge

Once the usual back-and-forth review process begins, reviewers make comments and requests for changes, and authors either accept them or make rebuttal. This process will be documented through comments and every piece of communication is tracked. Once everyone is satisfied, we make a collective decision to merge the pull request and it becomes a part of the master branch. Once this is done, we have several options. We can use several existing services to publish our repository directly as a website, or do something more sophisticated.

teamAt the Crossroads of Risk Factors

April 1, 2021In June of 2020, the executive director of the Texas Justice Initiative, Eva Ruth Moravec, started noticing a disturbing trend in the custodial death data - an alarming number of Texas Department of Criminal Justice's announcements about deaths by COVID-19 were coming from the same unit. In fact, of the 48 incarcerated individuals who died from COVID-19 in state-operated prisons and jails in June 2020, 14 were from the Duncan Unit. To put this another way: a unit that housed 0.3% of the state's prison population was suddenly reporting nearly 30% of the COVID-19 deaths that month. Together with Margarita Bronshteyn, one of TJI’s data scientists, Eva Ruth set out to understand what was driving this mortality rate and to shed light on those who died behind bars due to the pandemic, not a life sentence.

The Rufus H. Duncan Unit is a minimum-security lockup and one of Texas’ dedicated geriatric prisons. In June, the Duncan Unit housed just over 400 inmates - nearly all of whom were 55 years old or older. For many of those housed in the Duncan Unit, the intersection of incarceration and older age (often coupled with pre-existing conditions) proved to be one of many factors that put them particularly at-risk when it came to contracting and getting seriously ill from COVID-19. In just four weeks, the virus had infected 70% of the Duncan Unit's inmate population and one-third of its employees. As the summer wore on, TDCJ changed the way it reported data and TJI was unable to tell the total percentage of people who'd been infected at a particular unit.

Jeremy Desel, a TDCJ spokesman, stressed that the high positivity rate stemmed from the frequency and large scale effort when it came to testing those incarcerated in Duncan Unit. When asked about the mortality rate in particular, Desel said:

“If you look at our offender deaths — and actually, to be completely honest, our staff and offender deaths — if you look at them, across the board, there are very, very few that are not higher-risk folks, in that they have pre-existing conditions and/or are older. So you’re going to see, I think, a higher number of those instances in the older population units like Duncan.”

This past year was not the first time that the vulnerability of older, incarcerated individuals has come to light. A 2018 TDCJ employee publication reported that individuals 55 and older access in-prison health care five times more frequently than the rest of the incarcerated population. The article quoted Dr. Lannette Linthicum, director of TDCJ’s Health Services Division: “If they’re 55, they usually have the physiology of a 65-year-old, due to things such as lack of preventive health care, and behaviors such as alcohol and IV drug abuse.”

However, as people age, they also become far less likely to offend. Developed nearly four decades ago by Travis Hirschi and Michael Gottfredson, the “age-crime curve” has been a guidepost for assessing the likelihood of a returning citizen reoffending. Hirschi and Gottfreson found that, regardless of the person’ sex, criminality spikes between the ages of 12 and 25 after which there is a steep decline until reaching near-zero numbers by the age of 55. According to this model, the overwhelming majority of those incarcerated in the Duncan Unit would pose little to no risk to society upon release.

In fact, more than two-thirds of the Duncan Unit was parole eligible as of July 2020 and most of them (208 of 270) had been parole eligible for more than a year. Of the 21 men who died after contracting COVID while serving time in the Duncan Unit, 13 had served at least half their sentence, 17 were eligible for parole, and all were over the age of 60. Among these men were Jose Faide Morones, 70, who had completed his sentence but was denied parole in May of this year; and Jimmy Ray Price, 82, who’d served 24 years on a 25-year sentence and had been eligible for parole for 11 years, but was denied parole last spring.

So why were parole-eligible individuals not being released? According to Desel, additional measures, such as weeks-long precautionary lockdowns, were used to stop the spread of the virus and these lockdowns meant that everything came to a grinding halt. Movement was restricted and individuals were kept away from courses that are required for release on parole. Although TDCJ did resume the classes in late June, it has been a slow process. “[I]t’s going to be a long ordeal,” a woman who volunteers with the Texas Inmate Families Association told TJI. “A lot of these gentlemen are elderly and may not have any family left.”

Facilities in other states like New York and Illinois began releasing some of their incarcerated population in March after experiencing widespread outbreaks. In both states, the age-crime curve informed their decisions regarding whom to release. While New York prioritized releasing offenders over the age of 50 and Illinois prioritized those over 60, both states heavily weighed the presence of pre-existing conditions when reviewing cases for early-release. In both states, most releases have been the equivalent of 3rd-degree felonies or lower (see: Illinois’s IDOC spreadsheet for the full list of COVID-related releases). Researchers and reporters are no doubt watching to see if there are any spikes in crime associated with the release of offenders in either state – thus far, no publications suggest so.

incarcerationcovidThis is How We Watchdog

December 21, 2020We frequently mention that we “watchdog” the data that we work with as much as possible, but I thought I’d peel that back a bit. What do TJI’s oversight efforts look like?

Each month, I get new data from the Texas Office of the Attorney General reflecting the previous month's reported deaths in custody and shootings of and by law enforcement officers. I add this new data to TJI's main data sets. Overnight, bots look for changes to the data sets, which are then pushed through our processing pipeline.

The data-entry process is still quite manual, and I often find errors in the submitted reports – everything from misspellings and wrong names to transposed dates of death that result in negative ages and narratives obviously pulled from a different report. I note these, as well as missing reports – reports on shootings that were the subject of media coverage but were not filed within the required 30-day time period. I recently went through this process and wanted to document and narrate what this effort looks like.

First observation: There were quite a few custodial deaths in November – 144 deaths reported in that month alone, when we usually see around 90. Next, I noted a few missing custodial death reports:

- 11/5 fatal shooting of Reginald Alexander Jr. in Dallas;

- 11/18 fatal shooting of Pedro Martinez Jr. on the Tyler Junior College campus;

- 10/3 fatal shooting of Jonathan Price by Wolfe City police; and

- 10/9 fatal shooting of Ariel Esau Lujan by Houston police.

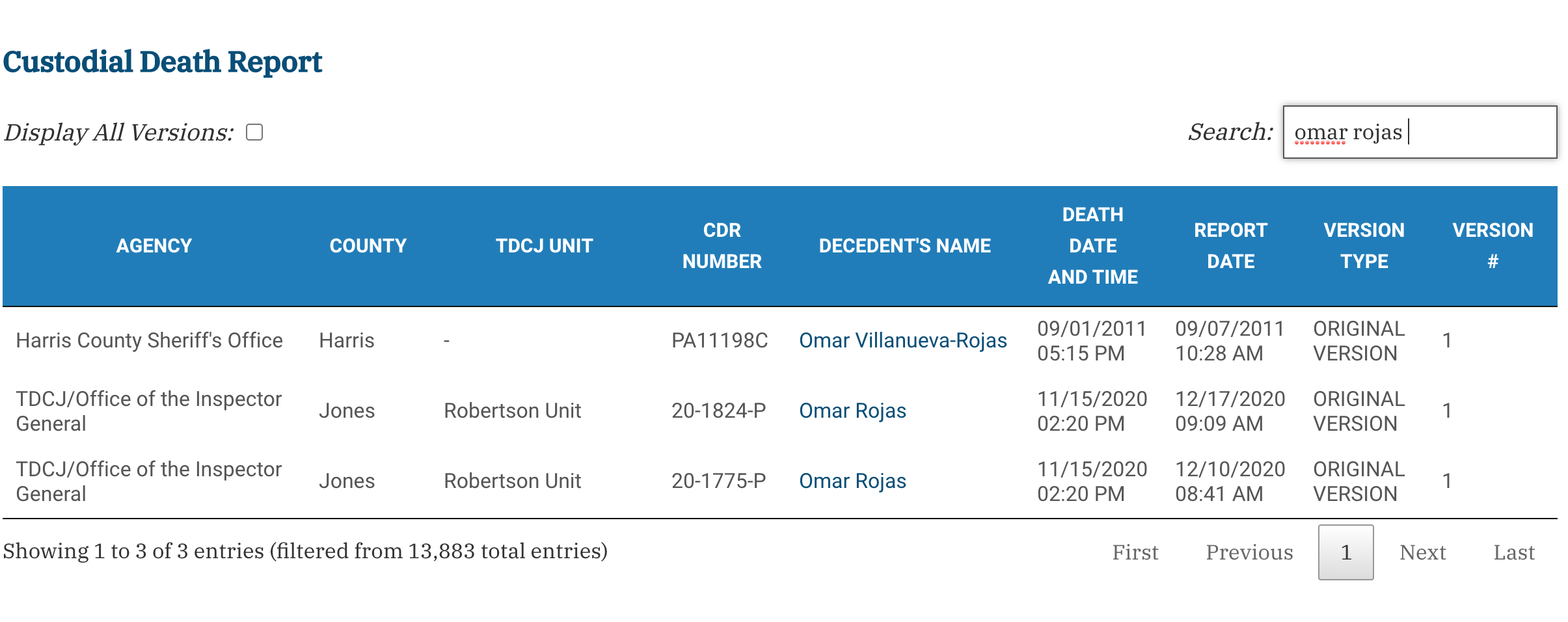

Then, I noted that there were two reports filed by separate people at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice for the 11/15 death of Omar Rojas:

And finally, the officer-involved shooting report for Reginald Alexander Jr. had been submitted by Dallas police, though media reported that he was shot by officers from another agency.

For each of these inconsistencies, I emailed the person at the agency responsible for filing the report and pointed out what I'd found. A couple immediately responded. One had misunderstood the law and filed the missing report that day, and another one said:

Hello Ma'am The officers involved do not work for the Dallas Police Department.

They are employed by the Dallas County community College system. They were unclear on whether or not they were set up to input information into the database.

I did not see a way to include in the drop down menu.

I will add the custodial death report because I do not believe that (they) have done so.

(I replied and advised that he run that by the OAG to be sure).

My best hope is that the agencies amend/file the reports, but if they don't, my only recourse is to point out to the Office of the Attorney General that the reports are missing. Even then, the OAG doesn't really have to take any action – they are merely a repository for those reports. Not filing a custodial death report is a Class B misdemeanor, states a law passed in 1983, though the punishment has never been used.

My approach, although toothless, often works. In 2020, agencies submitted 21 custodial death reports after I pointed out that the report was missing. But agencies can simply ignore my emails if they so choose, and then all I can do is tattle. It's great that Texas requires the collection of these reports, but watchdogging it can be a challenge, especially when the law has no teeth.

data oversightteam